The kimono, recognizable by its T-shape, flowing sleeves, and vertical panels draped over the wearer's shoulders, embodies Japan, both real and romantic, familiar and foreign. In the popular imagination, the kimono often represents an unchanging, traditional, and eternal Japan.

But how and when did the kimono become the national costume of Japan? Why is it more closely associated with the female body than the male? What processes led to the transformation of the kimono from an everyday garment to an icon of Japan?

Summary:

The Foundations of a Kimono Fashion Industry

The modernization of the kimono

Buying Kimonos: Shaping Identities

The kimono ideal migrates to the West

Kimono creators

From the Everyday to the Extraordinary, Yesterday and Today

The history of the kimono from 1850, just before Commodore Perry's American fleet arrived in Japan to force open its ports to international trade, to the present day, occupies largely unexplored territory. There are major gaps in our knowledge between the late Edo period, when the kimono was an everyday garment worn by many Japanese, and today, when it is mainly reserved for special occasions.

Major changes in the design, function, and meaning of this garment accompanied transformations in Japanese society, politics, economy, and international status. Within Japan, the kimono evolved from an object of everyday use to become an iconic Japanese brand. In Japan's colonial territories in the early 20th century, the kimono was worn by both the colonizer and the colonized, sending complex signals depending on who wore it.

Exported and adopted by consumers in Europe, Britain and America, the kimono functioned as both costume and clothing.

The Foundations of a Kimono Fashion Industry

The modern kimono fashion system grew out of the institutional foundations shaped in the early 17th century. At that time, the Tokugawa family rose to power, establishing a military government with its capital in Edo (present-day Tokyo) and organizing feudal domains into the semblance of a nation-state now recognized as Japan. The conspicuous consumption displayed through clothing choices revealed the tangled relationship between social and economic status in 17th-century Japan. In his book Japanese Family Storehouse (1688), social satirist Ihara Saikaku lamented the large sums spent on luxurious clothing in pursuit of the desire to live above one's social station.

The Social System of the Edo Period

In the early 17th century, the Tokugawa family rose to power, establishing a military government with its capital in Edo (present-day Tokyo) and organizing the feudal domains into the semblance of a nation-state. During the Edo period, the four-tiered social ranking system placed the samurai at the top , supported by farmers who cultivated the land and provided basic necessities. Craftsmen who produced material goods were third in the social hierarchy, while merchants who traded in these goods occupied the lowest social status. Together, craftsmen and merchants were classified as "townspeople" ( chōnin ) and formed the basis of the urban economy.

Our collection of Japanese kimono for men

The evolution of fabrics and patterns

The fabrics and technology available at the time of production dictated the weaving, dyeing, and decorating techniques available to the textile artisan. Japan's encounter with the West from the mid-19th century onward profoundly affected the materials, production techniques, and value of the objects worn.

Pattern Books: Essential Tools

The first books of kimono patterns were published in 1666. About 170 to 180 were published between 1666 and 1820. Most of the images appearing in these books followed a standardized format with a woodblock print illustration featuring a kimono-shaped silhouette decorated with various patterns. In some publications, textual comments further specified dye colors, dyeing methods, and other decorative techniques for a particular design.

The role of merchants and artisans

Cloth merchants and kimono makers pressed weavers and dyers to develop new colors, decorative techniques, patterns, and compositions to satisfy their fashion-conscious customers. Pattern books served as both a design source for the kimono maker and a catalog of available goods for the kimono seller . The illustrations in woodblock-printed pattern books, which often bear publication dates, can be matched to existing garments.

The influence of social classes

Although the outward appearance of a clearly defined hierarchy masked significant economic disparities and contradictions, clothing visually distinguished classes. For example, farmers, who ranked second in the social hierarchy, wore clothing made of durable, inexpensive materials with sleeves that allowed for ease of movement. Peasants could rarely afford the luxurious silks worn by some wealthier, but socially inferior, townspeople.

This complex structuring of Edo society laid the foundations for a veritable kimono fashion industry, with its codes, rules and innovations, which would develop in the following centuries.

Women's summer kimono ( hitoe ) with cricket and cricket cage motifs, late 19th - early 20th century, resist dyeing, hand painting and silk embroidery on cotton ground.

Women's summer kimono ( hitoe ) with cricket and cricket cage motifs, late 19th - early 20th century, resist dyeing, hand painting and silk embroidery on cotton ground.

The modernization of the kimono

From the opening of Japan’s ports to expanded international trade in the 1850s through the 1890s, a wave of imported materials, technologies, and designs infiltrated Japan’s shores. Empress Shōken’s 1887 imperial memorandum, circulated in the newspaper Chōya, urged her fellow women to embrace Western fashion, with the caveat that they should support domestic manufacturers. This reveals the growing tensions faced daily by wealthy women who could choose from the myriad of Western and Japanese clothing styles available to them.

Western influence on the imperial court

The Empress generally wore Japanese clothing during the first decades of her husband's reign, from 1868 to 1886. She continued to wear Japanese-style clothing even after Emperor Meiji appeared in Western-style uniform in 1872. From around 1887, the Empress favored Western-style robes over kimono, even as her subjects continued to wear their traditional attire.

The Rokumeikan Era: A Pivotal Period

The period from 1884 to 1889, commonly referred to as the Rokumeikan ("Belling Deer Pavilion") era, represented the lowest point of Japanese costume among the elite. Proving that Japan was equal to Western nations became a priority for the country in its efforts to revise the "unequal treaties." The Rokumeikan building, designed by British architect Josiah Conder, symbolized the aspirations of the Japanese elite to be seen as equals to their British, European, and American counterparts.

The evolution of fibers and fabrics

The materials and technology available at the time of production dictated the weaving, dyeing, and decorating techniques available to the textile artisan. Japan's confrontation with the West from the mid-19th century onward profoundly affected the materials, production techniques, and value of the objects worn. Japan domesticated foreign technologies and materials, harnessing the power of the West to fuel its textile industry.

Adaptation of foreign techniques

Rather than adopting or copying Western tools and concepts wholesale, as is commonly assumed, Japanese weavers and dyers exercised an adaptive and innovative approach to modernizing the kimono industry . International expositions offered the Japanese government the opportunity to promote its country's products and industry as well as to acquire new technologies and materials from the West.

The emergence of a new industry

The infrastructure established during the Edo period provided fertile ground for the stimulus activated by foreign materials and technology. Members of Japanese delegations sent to the United States and Europe conducted research abroad and returned with knowledge of new materials, tools, and technologies. This modernization allowed Japan to develop a unique kimono industry, combining tradition and innovation.

Our collection of kimono jackets for women

Buying Kimonos: Shaping Identities

Okakura Kakuzō, an influential teacher and cultural critic who served as a translator of Japanese art and aesthetics to the English-speaking world, observed in 1904 that a reactionary sentiment toward "things Western" had taken hold in Japan. This growing sense of national pride is not surprising, given that Japan had nine years earlier defeated its larger Asian neighbor in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95 and was mired in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05.

A new commercial era

The newly established department stores of the early 20th century helped consumers navigate the tides of domestic and foreign merchandise. Department stores used marketing strategies to establish themselves as the new arbiters of taste in modern Japan. Unlike the conventional kimono stores of the earlier Edo period, where shop boys retrieved bolts of silk for individual customers to examine, early 20th-century department stores were showrooms where merchandise was displayed in glass cases.

The role of department stores

Echigoya, which later became Mitsukoshi, continued to lead the way in stimulating demand with new advertising strategies. Mitsukoshi sponsored poster design contests that showcased the upcoming season's fashions. In an updated poster of promotional materials, Mitsukoshi's in-house magazine featured a woman in a kimono sitting on a chair surrounded by Art Nouveau-inspired interior designs and furniture , leafing through a woodblock-printed book with images of Edo-period figures.

The evolution of trends

Emerging designers, notably Sugiura Hisui, himself a collaborator in promoting a fusion of Japanese and Western aesthetics in the pages of Venus magazine, left their mark on the graphic arts and forged new directions in consumer trends. Hisui, who became Mitsukoshi's chief designer from 1910 to 1934, and Takahashi Yoshio, Mitsukoshi's director, are credited with Mitsukoshi's 1905 marketing campaign to revive the Genroku style.

Modern Female Identity

In the 1910s, many artisans began to grapple with the circumstances of anonymity and individuality, and engaged in debates over the distinctive characteristics of "craft" and "art." Modern kimono designs reflect the multifaceted roles of women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In this transitional era, working women were typically employed as waitresses in city cafes, saleswomen, textile mill workers, office workers, telephone operators, teachers, or nurses.

The emergence of a new clientele

Another category of consumers were urban middle-class wives. The model of the "good wife, wise mother" ( ryōsai kenbo ) often wore a kimono. The "ordinary woman" ( tada no onna ) wore traditional and familiar kimono patterns so as not to draw attention to herself. Her more liberated and modern sister, the emerging "modern girl" ( modan gaaru ), might on occasion choose to wear a fashionable kimono with her hair moderately permed in a Western style.

The kimono ideal migrates to the West

While the fictional Mr. B expressed a romantic notion of the kimono, Commodore Matthew Perry's assessment of Japanese women's clothing nearly 100 years earlier was less flattering. Perry described the women who served him in the Yokohama mayor's household as

"barefoot and barelegged, dressed very similarly in a sort of dark nightgown held up by a wide band passing around the waist."

Early Western Perceptions

Two centuries before Perry's arrival, the Portuguese Jesuit João Rodrigues had a similar impression of the kimono. While Perry recognized distinctions of rank based on dress, Rodrigues observed that the kimono was a long garment like a nightgown, once reaching the mid-leg or shin, but was now considered more elegant and formal to be worn to the ankles.

The influence on Western art

Visual sources from the mid-19th century reinforced the Western perception of the kimono as a dressing gown or bathrobe. In 1864, James Tissot completed the painting "The Japanese Woman Bathing." In the painting, a Caucasian woman emerges from the bath, draped seductively in a highly realistic reproduction of a kimono. This type of garment, decorated with a specific assortment of embroidered patterns in silk and gold thread, was a formal garment worn by wealthy women of the military class.

Cultural transformation

But what happens when one culture appropriates an object from another? In its new context, divorced from its social, economic, and political meaning, the object takes on a new life. In Tissot’s rendering, for example, the prized dress of a wealthy Japanese woman from the elite military class has crossed the globe from Japan to Europe. In its new context, the kimono has become a novelty. In the imagination of a European painter, the kimono is used to embody an exotic Japan.

Western designers draw inspiration

The kimono has influenced many Western designers, including Paul Poiret and Madeleine Vionnet. Poiret is known for freeing women from the constraints of corsets and petticoats, drawing inspiration from the kimono's straight cut. Vionnet, on the other hand, is known for her garments that fold, wrap, or drape around the body. Her iconic bias-cut dress, launched in 1919, was inspired by the principle of minimizing fabric waste, as with the kimono.

Commercial export

Japanese department stores such as Takashimaya also recognized a potential market for kimono as souvenirs. An early example of a Takashimaya kimono designed for export, purchased by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, is made of crepe silk (chirimen) fabric, similar in texture and design to a roll of crepe silk chirimen fabric exhibited at the Paris Exposition in 1867. Unlike kimono for Japanese consumers, this kimono had additional panels inserted into the side seams that effectively widened the skirt area, and a loop inside the collar to facilitate hanging on a hook.

Kimono creators

From the 1910s to the 1990s, a wave of imported materials, technologies, and designs infiltrated Japan. Kimono designers emerged as individual artists, moving away from the tradition of the anonymous craftsman. This development was supported by department store and government-sponsored competitions, as well as awards and honors bestowed on individuals rather than groups.

The war period and its impacts

In the 1940s, the Japanese government targeted textile manufacturers, regulating their production. In July 1940, the government enacted a law restricting the manufacture of luxury goods. Soon after, slogans declaring "Luxury is the enemy" began appearing on the streets. Luxurious kimonos were among the many luxury goods regulated. Textile materials became so scarce that some Japanese were reduced to wearing fabrics made of cotton mixed with bark and wood pulp (sufu).

Living National Treasures

In 1955, the Japanese government instituted a system for designating individual artisans as "holders of intangible cultural properties." Today, recipients of this honor are more commonly referred to as Living National Treasures ( ningen kokuhō ), the government's highest honor for artistic achievement. Tabata Kihachi III, Serizawa Keisuke, Inagaki Toshijiro, Moriguchi Kakō, and his son Moriguchi Kunihiko are just a few of the many textile artisans who have enjoyed this status.

An iconic designer: Uno Chiyo

Uno Chiyo (1897-1996) was a pioneer. She is described in her biography as a "fashion ingénue, magazine editor, kimono designer, and celebrated femme fatale." Her life—several divorces, financial independence, and commercial success as a writer—was atypical at a time when women were encouraged to lead lives modeled on the role of "good wife, wise mother." In 1949, at the age of 52, Uno established a research project on the kimono and began publishing, as part of "Style," "Kimono Primer" (Kimono dokuhon).

Our collection of kimono for women

Itchiku Kubota: innovation in tradition

Itchiku Kubota (1917-2003) was an innovator in the world of kimono. Inspired by a 16th-century textile fragment seen in a museum display case, Itchiku sought to revive the aura and techniques of one of Japan’s most revered dyeing traditions—commonly known as tsujigahana. In his most ambitious series, “Symphony of Light,” the kimono transcends the traditional confines of a wearable garment and emerges as an installation work.

Our collection of kimono for men

The Moriguchis: A Dynasty of Creators

Moriguchi Kunihiko , designated a Living National Treasure in 2007, followed in the footsteps of his father Moriguchi Kakō, who was designated a Living National Treasure in 1967. In the world of traditional Japanese crafts, this is the first time that a father and son have received the designation during their shared lifetimes. Unlike his father, who favored abstraction of nature's motifs, Kunihiko draws on his background in graphic design to guide his creative process. He designs on paper, each meticulously hand-drawn. His designs lean toward the geometric and play with optical illusions, infusing the kimono format with a whole new genre of pattern.

From the Everyday to the Extraordinary, Yesterday and Today

"If you are afraid to wear the kimono, don't be... Why am I Japanese, why? I never wanted to be. There was never a choice. I was just born in Tokyo."

This reflection by contemporary fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto perfectly illustrates the complex relationship that modern Japan has with the kimono. Through these words, the designer encourages us to rethink the rigid conventions surrounding the wearing of the kimono and proposes a freer and more contemporary approach to this traditional garment. This tension between tradition and modernity, between yesterday’s everyday and today’s extraordinary, characterizes the evolution of the kimono in contemporary Japanese society. From an everyday garment, the kimono has gradually transformed into a cultural symbol, carrying a national identity while adapting to societal changes and international influences. This chapter explores this fascinating transformation, from the postwar period to the present day, revealing how the kimono continues to reinvent itself while preserving its cultural essence.

Post-war transformation

During the 1940s and 1950s, the kimono underwent a profound transformation in its status. The Japanese government, faced with wartime shortages, imposed the kokuminfuku ("people's clothing"), a more practical and economical outfit. This period marked a decisive turning point where the kimono, once an everyday garment, gradually became a ceremonial garment. Indeed, many families were forced to exchange their precious kimonos for food on the black market, giving rise to the expression "bamboo existence" (takenoko seikatsu), evoking the need to shed one's clothes like layers of a bamboo in order to survive.

The imperial and commercial revival

The marriage of Prince Akihito in 1959 marked a major turning point in the perception of the kimono. The many photographs of the future Empress Michiko in kimono revived popular interest in this traditional garment. Japan Airlines capitalized on this trend by dressing its first-class flight attendants in kimono starting in 1954, using the garment as a symbol of distinctive Japanese elegance. In 1959, Akiko Kojima's victory in the Miss Universe pageant, often photographed in kimono, further reinforced this positive image internationally.

The institutionalization of wearing the kimono

The 1960s saw the emergence of a new approach to kimono with the establishment of specialized schools. Yamanaka Norio, a pioneer in this field, founded the Sōdō Kimono Academy in 1964. These institutions developed a strict set of rules regarding the wearing of kimono, its accessories and etiquette. What was once a natural and everyday practice became a codified art requiring formal training.

The role of department stores

In the post-war period, Japanese department stores assumed a crucial role in preserving kimono culture. They became not only places of sale but also centers of education, teaching new generations the art of wearing kimono. This period also saw the emergence of a "retro boom" in the 1980s and 1990s, characterized by a nostalgic return to traditional and rural values.

Contemporary revival

Today, the yukata, a more casual summer version of the kimono, is experiencing a significant revival. Particularly popular during festivals like Obon, it has become more accessible thanks to retailers like Uniqlo offering pre-packaged versions with matching obi. Events like "Ginza Kimono" and "Jack Kimono," where participants gather in kimono on the streets, are showing a new interest in this traditional garment that transcends national and cultural boundaries.

Modern adaptation and international perspective

The collaboration between fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto and traditional kimono house Chisō is a perfect example of how the kimono is adapting to the modern era. Yamamoto encourages a freer and more creative approach to kimono wearing, moving away from traditional strict rules. This evolution reflects a broader trend where the kimono is finding its place in a global context while preserving its Japanese cultural essence.

Japan Tourism Bureau, 'Cool Japan' campaign poster featuring pop stars Puffy AmiYumi, 2006

Japan Tourism Bureau, 'Cool Japan' campaign poster featuring pop stars Puffy AmiYumi, 2006

Sumo: The Japanese Wrestling Sport

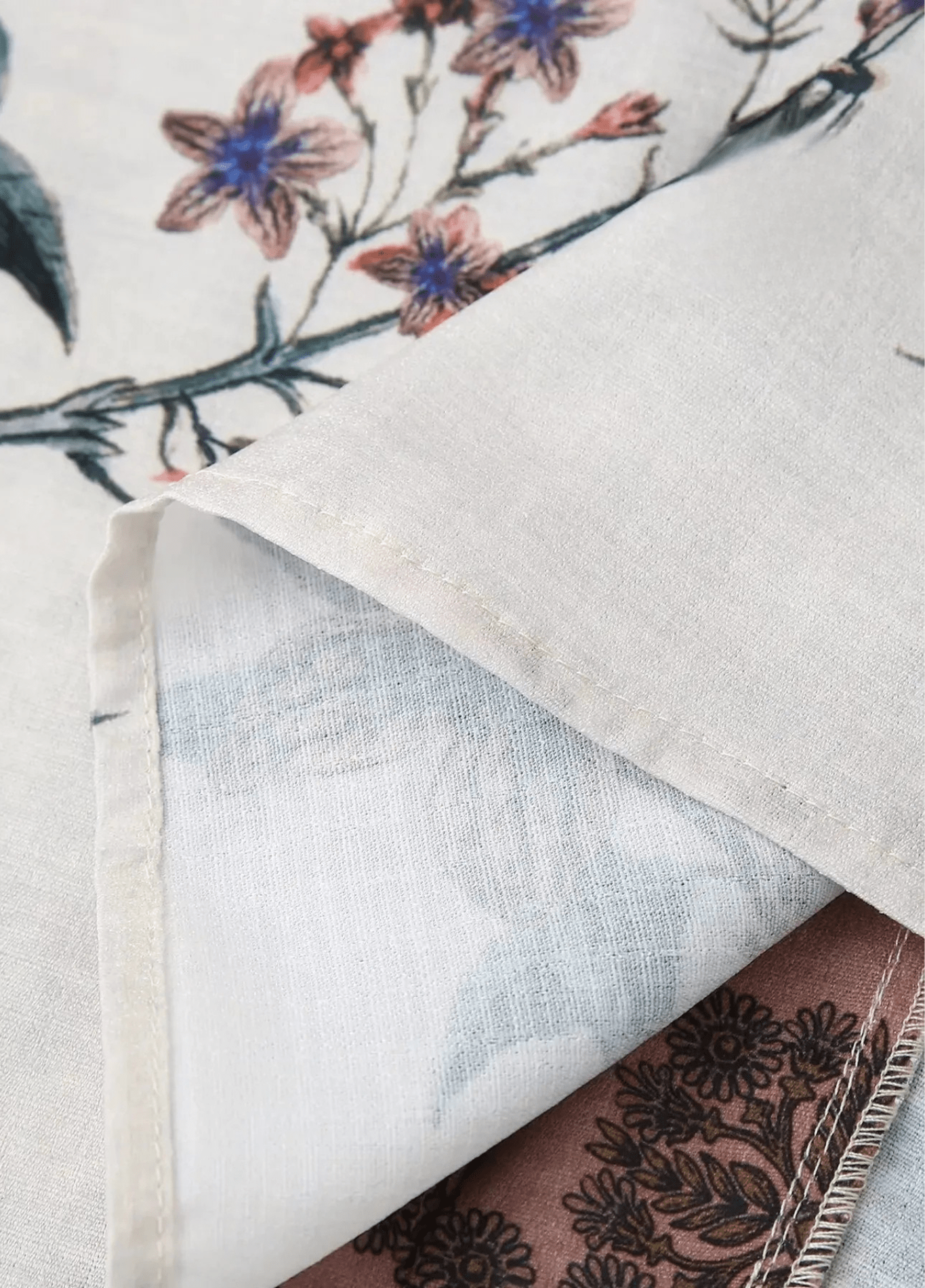

Long Japanese print kimono

Long Japanese print kimono